Monday, June 29, 2015

Seen any good disaster movies lately? This story is better, and as Henry Kissinger liked to say, it has the added benefit of being true. In three days, the earthquake and ensuing fires killed thousands, left hundreds of thousands homeless, and almost destroyed San Francisco. It is a story of heroism, decency, bad luck, dumb luck, ingenuity, incompetence, corruption, greed, racism, brutality, and political recrimination, for starters. One hundred years later, what have we learned (and not learned)? Bob Cherny, an authority on turn-of-the-century San Francisco, was our guide. A professor emeritus at SF State and the author of numerous books and articles on the period, Bob gave a superbly organized lecture and slide show to tell the tale and explain its significance. It was entertaining, but it wasn’t Hollywood. Afterward, we actually knew something useful.

In April 1906, San Francisco was a thriving city of 342,000. It was the ninth largest city in the country, the second largest west of the Mississippi (behind St. Louis), and by far the largest and most important in the West— more than triple the size of Los Angeles. San Francisco’s banks financed economic development throughout the West. The Southern Pacific Railroad, which had its headquarters in San Francisco, was the biggest landlord in California and commanded the largest transportation network in the country. SP had a virtual monopoly on railroad travel (including within the city itself). It owned 16,000 miles of shipping lines in addition to 9,000 miles of rail lines. More boatmen and seafarers lived in San Francisco than in any other city. The Ferry Building was the second busiest in the world. San Francisco was also a manufacturing center, with food processing, metal working, clothing, and shoe factories. The city’s Union Iron Works employed 1,200 workers in 1890. In 1888, Englishman James Bryce wrote that California was a country by itself and that San Francisco was its commercial and intellectual center.

Bob showed us a five-minute film taken four days before the earthquake: “A Trip Down Market Street.” Shot from a vehicle moving down Market Street toward the Ferry Building, the film captures the energy of the city: new steel-framed buildings, electrified and horse-drawn streetcars, horse-drawn carriages, the occasional horseback rider, automobiles (that new toy of the wealthy), bicycles, and formally dressed pedestrians, all skittering along a cobble-stoned Market Street without the benefit of traffic controls and with more energy than order. Vehicles and people zig-zag and dart. Street cars don’t stop; passengers (including women in long skirts) had to hop on and off.

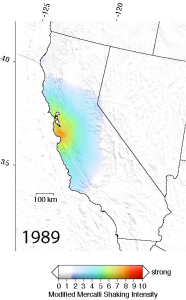

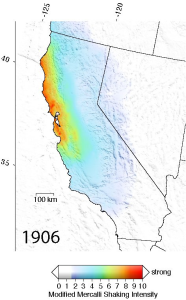

Then the earth moved. At 5:12 a.m. on April 18, 1906, two adjoining tectonic plates slipped just west of San Francisco, producing an earthquake today estimated at between 7.7 and 7.9 on the Richter Scale. It was 45 times more powerful than then 6.9 magnitude Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989. The shaking extended for some 270 miles, and the earth moved as much as 25 feet.

Most of the city’s buildings survived the earthquake. But the shaking broke gas and water mains, causing disaster: fire and the crippling of the water system designed to suppress it. Some fifty fires broke out south of Market and quickly spread to the central business district and the Mission. The fires soon became a firestorm. Jack London, who sailed to the city in his sloop to cover the event, wrote that half the heart of the city was gone in twelve hours, as the fire “built its own chimney.” However, “there was no disorder, no panic. Never were people so kind as courteous as people who fled the city.”

Brigadier General Frederick Funston was the acting commander of the federal troops at the Presidio. Acting on his own initiative and without any legal authority, Funston marched the troops into the city “to aid the municipal authorities. . . .” Mayor Eugene Schmitz welcomed the decision and ordered the troops and the police to shoot looters. In effect the city was under martial law.

It did not go well. In an attempt to prevent looting, the authorities ordered residents off the streets, a blunder because the order discouraged people willing and able to fight the fires from doing so, although many pitched in anyway. The troops and police targeted poor people and ethnic minorities with their “shoot to kill” orders. Some of the soldiers and police officers themselves looted.

In the absence of a functioning water supply, the authorities tried to create fire breaks with dynamiting, but the explosions may well have made the fires worse because the crews did not know how properly to use dynamite.

Some of North Beach was saved by residents who soaked blankets in red wine and covered their buildings. Water pumped from the bay saved the waterfront. One building there that survived was the warehouse of Hotaling’s Whiskey, which led to this bit of doggerel: “If, as some say, God spanked the town/ For being frisky/ Why did He burn the churches down/ And save Hotaling’s whiskey?”

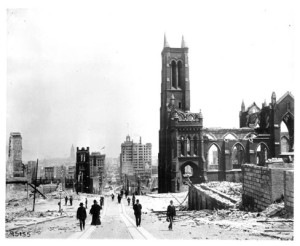

This short article summarizes the earthquake and fires and includes some short clips from films taken in the aftermath. The thriving metropolis from the earlier film has become a devastated war zone. Four square miles of the city, 28,00 buildings, and three-quarters of its residences were destroyed. City leaders kept the official casualty count low because they didn’t want the the world to know the extent of the disaster, but years later, the research of city librarian Gladys Hansen established that about 3,000 people died and 225,000 of the city’s residents were left homeless. Many of the homeless were housed in 5,610 tiny earthquake shacks (as small as 16 feet by 10 feet), 23 of which remain today. The fires destroyed 80% of Adolph Sutro’s invaluable collection of 500,00 books.

A. P. Giannini did better. The owner of a tiny bank in North Beach with loans that far exceeded its deposits, Giannini used two wagons to carry the bank’s $80,000 in gold and silver to his home in San Mateo. While bigger banks couldn’t open their vaults after the fire because the contents would have spontaneously combusted, Giannini had the cash to start making loans in a town desperately needing money to rebuild. He set up shop with a bag of gold prominently displayed on a plank laid over two barrels near the waterfront. Thus began the Bank of America.

Not wanting to lose its place as the West Coast’s center of economic and political influence, San Francisco rushed to rebuild. Rejecting an ambitious (and impractical) plan to redesign the city (the Burnham Plan), the city re-established its street grid almost exactly as it had been before the earthquake. In a triumph of greed over racism, the Chinese were permitted to remain in Chinatown because it was financially advantageous for whites to allow them to remain.

For more on the earthquake, fire, and their aftermath, see Philip L. Fradkin’s definitive volume, The Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906: How San Francisco Nearly Destroyed Itself.

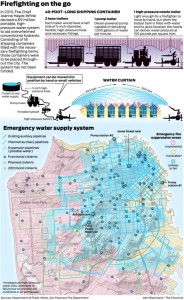

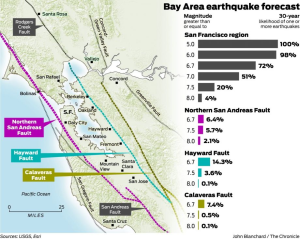

After the 1906 disaster, the city constructed a state-of-the-art three-tier water supply system that is still in use today. Yet concern remains over the city’s fire-fighting capability after an earthquake. The 1989 earthquake ruptured water mains in the Marina. That neighborhood would have been lost if not for water pumped from the bay. As shown by the graphics below, a severe earthquake, and quite possibly a bigger one, will strike the Bay Area in the next thirty years. As in 1906 and in 1989, the most vulnerable areas are those built on landfill or over underground creeks.

According to this article in the Chronicle, the city’s in-place system of water supply failed again in 2014 during a big fire in the Mission Bay area. Firefighters needed a portable auxiliary hose system to extinguish the fire. The article reports that the city has only two such portable systems and that the fixed systems leave large parts of the city uncovered. As indicated by the graphic below, the two portable systems may not be adequate to extinguish the many fires that likely would break out after a major earthquake and would be beyond the reach of the fixed system, especially if it were damaged.

————-

Bob Cherny is a scholar who specializes in American political history from the Civil War to World War II and in the history of California and the West. He received his PhD from Columbia University in 1972 and taught at San Francisco State University from 1971 to 2012. He has been an NEH fellow, a Distinguished Fulbright Lecturer at Lomonosov Moscow State University, a visiting research scholar at the University of Melbourne, and a senior Fulbright lecturer and researcher at Heidelberg University. In addition to more than thirty published essays in journals and anthologies, mostly about the history of politics and labor in California and the West, he was written three books on U.S. politics from 1865 to 1925. He is co-author of two books on the history of San Francisco, a U.S. history survey textbook now in its seventh edition, and a California history textbook now in its second edition. He has co-edited two anthologies—one on U.S. labor during the Cold War, the other on California women and politics. His most recent work, soon to be published, is a biography of Victor Arnautoff, the San Francisco artist who in the thirties created the murals at Coit Tower and George Washington High School, as well as murals elsewhere in the Bay Area.