Monday, November 30, 2015

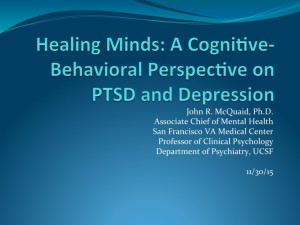

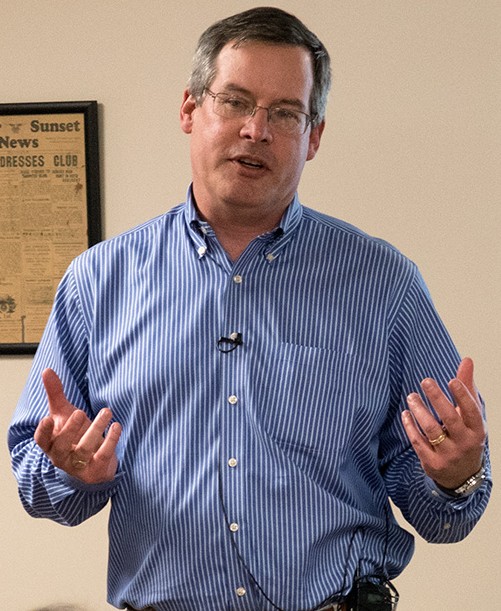

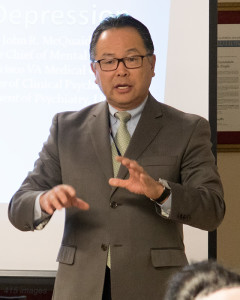

Depression afflicts millions, yet it can be treated, often without medication. SHARP heard from an expert in the field, John R. McQuaid, Ph.D., who has been studying and treating depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for more than twenty years. McQuaid is a prominent figure in psychotherapy research, a professor of clinical psychology at UC San Francisco, and the Associate Chief of Mental Health for Clinical Administration at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SFVAMC). In 2004, he co-authored a guide for laypersons: Peaceful Mind: Using Mindfulness and Cognitive Behavioral Psychology to Overcome Depression. In other words, he knows what he’s talking about, and you don’t need a degree to understand him. In his talk at SHARP, he explained depression and PTSD, including the latest research about them, and used case examples to describe treatments that work, including what patients do for themselves. The patient does have to work, but sometimes it doesn’t feel like work because of the pay-off, and sometimes it’s literally fun. Non-blinding insight now supported by research: having fun is therapeutic.

THE SAN FRANCISCO VA MEDICAL CENTER

The evening began with a brief introduction to the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) from Bob Obana, the Executive Director of the Veterans Health Research Institute (also known as NCIRE, for Northern California Institute of Research and Education) at SFVAMC. NCIRE sponsors a yearly conference on veterans’ health, which Obana said is free and open to the public. Here is a summary of the 2015 conference.

Because of its integration with UCSF, SFVAMC is not only the leading and largest research facility in the Department of Veterans Affairs but one of the nation’s leading academic medical centers. All UCSF medical students, residents, and fellows rotate through SFVAMC, which provides nearly one-third of UCSF’s medical training. Like Dr. McQuaid, every staff physician in the SFVAMC’s Medical Service is also a full faculty member in UCSF’s Department of Medicine. Here is an article about innovative treatment at SFVAMC of PTSD.

JOHN McQUAID’S TALK AND BOOK

The summary below covers McQuaid’s talk and key principles from Peaceful Mind.

This wonderful summary of the talk itself comes from a member of the audience and first-time visitor to a SHARP meeting, Rachel Buddeberg. Her summary includes helpful links. Thank you, Rachel!

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

McQuaid uses Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to treat patients who suffer from depression or PTSD. CBT rests on the premise that the way in which a person responds emotionally to a situation depends on how she thinks about it. Since people who are depressed have a distorted view of their experiences, CBT helps a depressed person to reinterpret her experience in a way that is more accurate and helpful. In that way, CBT begins to change thinking (cognition) and actions (behavior) to change emotions such as depression.

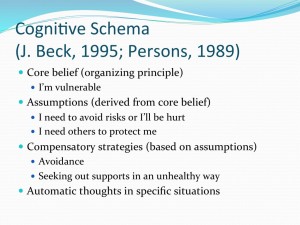

Every person has a four-tiered framework of thoughts (a “cognitive schema”): (1) organizing principles, called “core beliefs”; (2) assumptions based on the core beliefs; (3) compensatory strategies based on the assumptions; and (4) automatic thoughts. Peaceful Mind says core beliefs “are like hidden groundwater that runs deep beneath the earth, invisibly feeding all of your assumptions, strategies, and automatic thoughts.” (P. 49.) Assumptions are “the rules you make for how you conduct yourself based upon your core beliefs. . . Whereas core beliefs may not be at a conscious level, assumptions typically are. . . .” (P. 52.) Strategies are “defensive styles or chronic behaviors that protect [a person] from feeling the pain of a core belief. . . . They are logical actions given your core beliefs and assumptions.” (P. 53.) Automatic thoughts “dart across your mind in response to all the . . . issues of your life, sometimes fighting your basic strategies and sometimes just moving with the current of your strategy.” (P. 55.)

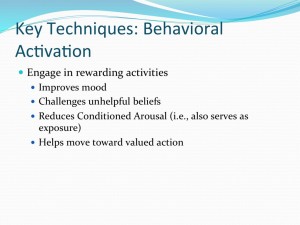

(Text graphics are slides from the talk, not from the book. Click on graphic to enlarge.)

A depressed person might have a core belief that he is vulnerable. That belief might lead to the assumptions that he needs to avoid risks or needs others to protect him. Those assumptions might produce strategies such as avoidance or seeking out support in an unhealthy way. He may have an automatic thought such as “Who can help me?” (P. 59.) CBT is partly a process of observation by which a person identifies his core beliefs, assumptions, strategies, and automatic thoughts in order to understand them and make them more accurate. More accurate thinking dissipates depression. Reality, it turns out, is good for your mental health, or at least a lot better than the distorted notions a person usually has when depressed.

McQuaid gave the example of a veteran who considered himself weak because he was having panic attacks. Asked by McQuaid for evidence that might counter this belief, the veteran said it took courage for him to share his belief that he was weak, and he had been courageous, too, in asking his wife for support. The veteran undermined an inaccurate, detrimental core belief of his by producing evidence that refuted it.

Peaceful Mind (p. 14) describes CBT as the following process: “First you learn to observe your thoughts, actions, and feelings and see how they influence each other. You then identify those thoughts and actions that seem to cause you to feel more depressed and learn to check them out. You question whether the thoughts are true and accurate or whether they actually mislead you [emphasis added] and increase your depression. You check whether your activities are making you feel worse and whether you might be able to do different activities that improve your mood. Next, you experiment with new thoughts and new activities. You develop new, more accurate thoughts based on the evidence you see around you, and check to see if the thoughts lead to a better mood. You try doing old activities differently or try new activities, and see if these improve your mood.”

Mindfulness Through Meditation

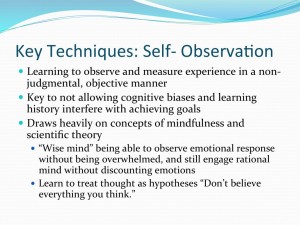

To be able to see oneself more clearly—one’s core beliefs, assumptions, strategies, and automatic thoughts—it is necessary to cultivate a dispassionate state of mind called mindfulness, or nonjudgmental awareness. McQuaid defined mindfulness as the act of observing in the present moment without judgment.

The practice of meditation enhances mindfulness by training the mind to focus on the present, see reality, and acknowledge emotions without letting them rule. “Meditation starts with simply observing the mind and body without necessarily trying to change what is seen or the seer. . . .” (P. 24.) “Self-observation is a skill. As with other skills, you practice to become competent. . . . Awareness grows by repeated practice of observing thoughts and emotions passing through the mind and body. . . .” (P. 26.) “In mindfulness meditation we do not try to escape to some blissful place—we stay with each moment. When we want to avoid staying with each moment, we notice that urge to avoid and literally sit with our avoidance. We carefully watch the thoughts that arise about not liking this moment. We feel the body resist this moment. As we stay with our resistance, we again exercise the muscle of awareness. However, building the muscle broadens the awareness. The awareness is no longer narrow and constricted; it is a wide awareness that allows us to be aware of our difficulties and of the broader environment. . . . From this place of expanded awareness you can watch your thoughts and impulses change and fade. You can develop the internal stability to watch the movement of your mind. . . . This broad, open awareness trains you to be aware of difficulties but also provides mental and physical training for you not to be locked into your misery. . . . Through the repeated training of meditation, you develop the skills to turn the mind and attention toward health and away from self-destructive thoughts and habits. ” (Pp. 26-27.)

“If you think of depression as a mental and physical resistance to being with the moment, you begin to appreciate how powerful it is to let the resistance be the teacher. This phrase, ‘letting resistance be the teacher,’ suggests having the capacity to tune into what is arising in the mind and body and allowing those thoughts and physical sensations to exist, rather than trying desperately to avoid them with perhaps alcohol abuse, the pursuit of a new purchase, or any number of avoidance behaviors that are widely available in our culture. Indeed, it’s the direct experience of the body and mind, whether it is the sensation of the warm open heart or the fear in the pit of the belly, which transforms our lives. . . .” (P. 27.)

McQuaid said that research has begun to show the positive effect meditation has on the brain. This article describes one such foray into the neuroscience of meditation: a study of the brains of Buddhist monks who were expert meditators.

Enhancing one’s ability to see oneself more clearly, meditation is one technique for improving one’s mood. But it isn’t the only one. Having fun also helps. McQuaid said that engaging in rewarding activities can be as effective as any other treatment. Apart from improving one’s mood, having fun debunks inaccurate, destructive beliefs about oneself, just as more accurate thinking about oneself enables a person suffering from depression to have fun in the first place.

McQuaid said he meditates 15 minutes a day at the start of the work day. He chose that time period because years ago it took his work computer almost 15 minutes to warm up. Sometimes the government works in weirdly wonderful ways. McQuaid uses a meditation technique he calls “leaves floating down a stream.” When (inevitably) thoughts arise in his mind as he meditates, he “sees” the thoughts as leaves floating down a stream, thereby letting them go instead of becoming absorbed by them.

A Case of Depression

McQuaid told us about a woman he treated for depression. She was 59 years old, divorced, disabled, and Native American. Diabetes and heart disease caused her to be confined to a wheelchair. She lived on a small fixed income of Social Security Disability in a one-bedroom apartment with a daughter, son, daughter-in-law, and three grandkids, including a four-year-old she was raising. In addition to depression, she suffered from anxiety, low energy, anger, difficulty staying awake during the day, appetite increase, weight gain, crying, guilt, shame, and hopelessness.

McQuaid asked her to prioritize her problems and identify her goals. She said she wanted to feel better, improve her health, resume activities she enjoyed (swimming and sewing), get the kids out of the house, and, most of all, be a good grandma.

She had a core belief that she was undeserving and unlovable. She assumed that she could not tolerate being abandoned (because then she would never get loved again) and that she had to sacrifice to get the love she needed. Her strategy was to be passive and to put others first.

McQuaid asked her to do things she enjoyed, but she wouldn’t. So he challenged her core belief that she was unlovable. She stated a religious belief that everyone is lovable, and she recognized that people in her life did love her. These realizations increased her self-esteem by weakening her core belief that she was unlovable.

McQuaid treated her also by helping her to identify her automatic negative thoughts and to learn and practice asking for what she wanted. She became more assertive by, for example, setting limits with the kids.

Her treatment lasted about nine months. Her depression improved from severe to mild; she got her teeth capped; the children moved out; and she returned to the activities that gave her pleasure: sewing and swimming.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD is an anxiety disorder in which trauma has conditioned a person to fear things he associates with that trauma, even when those things are benign. For example, a soldier who experiences the devastation of roadside bombs hidden in trash piles may become extremely anxious in civilian life when he encounters a pile of trash. He will try to avoid them, but they are everywhere, of course, so his strategy of avoidance makes him no less anxious, only more restricted and isolated.

To alleviate the condition, McQuaid works with the patient to place the trauma or loss in context, changing its meaning from a dominating memory to a part of one’s life that has passed. McQuaid exposes the patient to the memory of the trauma in a way that eventually defuses its power and allows the person to rediscover her belief in herself.

He told us of a 30-year-old African-American woman who had been raped by a white male. She asked to see a female therapist, but her request was mishandled, and McQuaid was assigned to her. Having avoided white men since the rape, she panicked when she first saw McQuaid. He offered her a female therapist but she declined. She said, “I guess this is God telling me I need to deal with this.” (Evidently, this rape victim had not surrendered entirely to avoidance.)

At first, McQuaid just sat with her, using an office in a busy hallway and keeping the door open. They did not discuss the trauma. In the third session, she said it was okay to close the door, and she was able to describe the rape in detail. In the sixth session she said, “I am going to get my life back.” In tolerating McQuaid, she had shown herself who she really was: a person capable of tolerating stress.

As with depression, the treatment of PTSD modifies a person’s thoughts and beliefs by allowing the person to realistically examine her experience.

——-

After his talk, McQuaid responded to a variety of questions and comments. When the meeting ended, he stayed to answer still more questions. He was pretty much the last person to leave. He did not address the importance of having a therapist who communicates caring, but he demonstrated it.